There is a segment of the technology and venture capital communities that believe a lack of access to the venture capital asset class is a major disadvantage to the individual investor. The story tends to go something along the lines that venture capital has tremendous returns and the barriers to investment are limiting the wealth building capabilities of individuals while favoring wealth accumulation for the very rich. An example comes from Fred Wilson’s blog post on May 5th, 2021 titled Half of All VCs Beat The Stock Market. Fred closed his post with the following:

“The VC market remains largely out of reach of many “main street” investors as the SEC limits these fund investments to qualified and accredited investors. That has never made sense to me and is yet another example of the “well meaning” rules resulting in the wealthy getting wealthier and everyone else missing out.”

– Fred Wilson

Alex Rampell and Marc Andreessen communicated a similar narrative during their interviews with Patrick O’Shaughnessy on Invest Like the Best. Each person mentioned is a better investor than myself and I would be thrilled if my career success was a fraction of their own, but I disagree with their view on this topic. There are also far less reputable individuals who are more aggressive about championing open access to venture investing and alternative assets in general.

I’m going to present a case that the story of accessing venture will improve the lives of retail investors is overblown as average venture returns aren’t clearly better than public market alternatives and illiquid assets often don’t address the challenges of the retail investor. Many of the considerations will apply to other private markets asset classes including private equity and real estate, so venture isn’t alone in my critiques, for those that believe access to these illiquid assets with make a meaningful change to the wealth generating ability of non-accredited investors.

Is The Performance Story Real?

Let’s start by looking at the investing outcomes of venture relative to more accessible liquid alternatives. My belief is the paper reference by Fred in his blog post from Harris, Jenkinson, Kaplan, an Stucke (“HJKS Paper”) dated November 2020 overstates the relative returns of the venture industry compared to public markets due to data biases and the existence of a more appropriate liquid investment benchmark than what is used in the piece. Please check out the paper if you want to dive deeper into the methodology and for interesting information on persistence of returns (along with conclusions favorable to emerging fund managers).

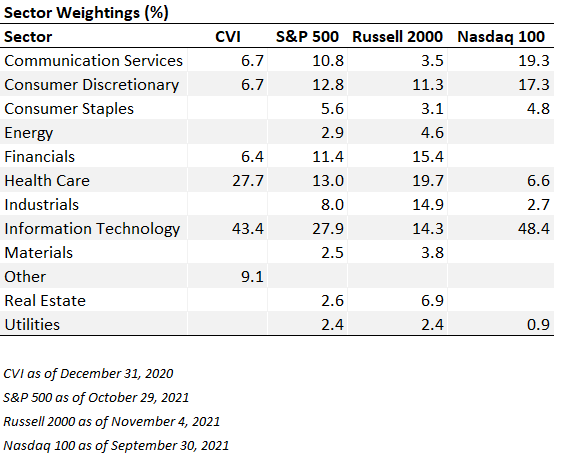

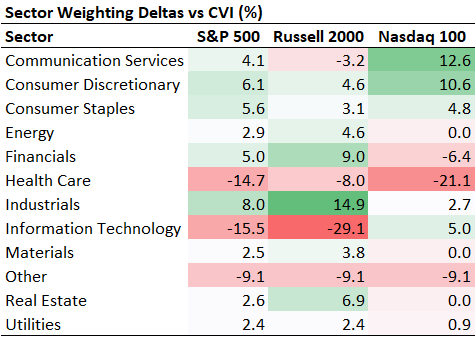

While the HJKS Paper uses the S&P 500 and Russell 2000 benchmarks to compare returns, the Nasdaq 100 (or QQQs) are a better proxy as a public market alternative given the underlying industry exposure. The S&P 500 and Russell 2000 have technology sector exposure well below that of the venture asset class at this time. Data below doesn’t account for historical differences (both potentially closer to or further diverging from the index). A more appropriate benchmark comparison will remove some of the delta in performance associated with the beta exposure to the underlying industries. Using Cambridge Associates data on the industry composition of the venture asset class, below is a table detailing the industry composition of the Cambridge Venture Index (“CVI”), S&P 500, Russell 2000, and Nasdaq 100. Also below is a table showing the delta between the CVI and the three public indexes. The Nasdaq 100 is likely the best proxy to the CVI out of the three options based on industry exposure.

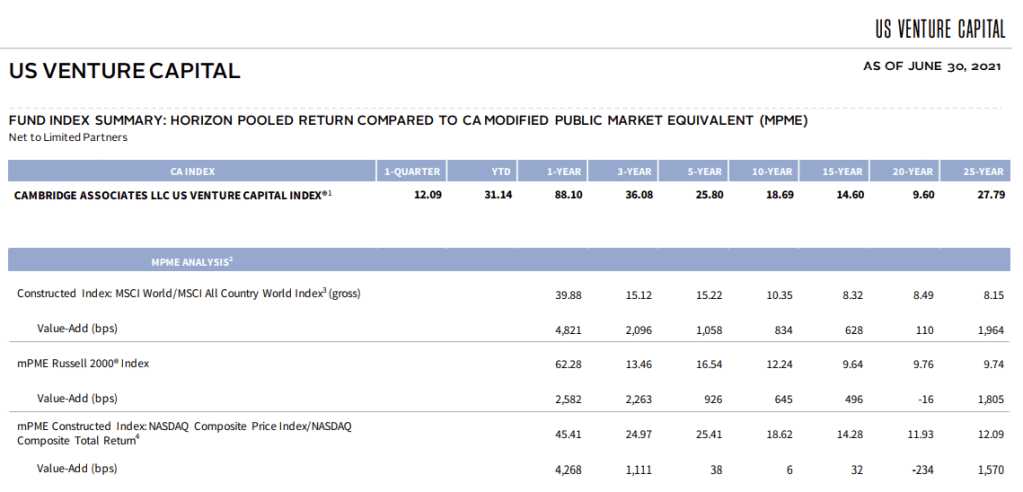

Returns data from Cambridge through June 2021 presents a mixed picture of performance relative to a more appropriate benchmark to account for industry betas. Cambridge’s Nasdaq Modified Public Market Equivalent (“mPME”) is a composite of the whole Nasdaq index, which should be roughly in-line with the Nasdaq 100’s performance given the disproportionate weighting of the largest 100 stocks on the overall performance. The 25-year window has spectacular returns for venture capital, which happens to include the tech bubble. The 20-year window has material underperformance relative to the Nasdaq mPME with roughly flat relative performance in the five, ten, and fifteen year windows. Venture outperformed in the one and three year time frames. The mixed record for the whole asset class calls into question how much benefit a retail investor would realize with venture exposure in their portfolios.

One could argue recent history entered a period where venture can continue to outperform given the scale and scope of businesses being created at this time. Relative to the twenty-year window, there would need to be a persistent shift in return outcomes going forward and not just a small window of venture excelling. I’m assuming the tech bubble window was a unique period and not something that would occur with enough frequency that those return outcomes are consistent enough to impact long run returns for investors. Twenty years is a long time to lag public alternatives. Carlota Perez’s work on technological revolutions could imply that if tech bubble level events do occur with some repeatable frequency, the cadence could be every fifty to sixty years. Near term outperformance by venture, the results of investments made years ago, may not continue unless the breadth and scope of the opportunity set is greater than the market’s drive to elevate valuations at all levels of growth investing. In my view, continued levels of excessive performance would attract more competition at higher prices as seen by the behavior of firms like Tiger Global that would drive down future prospective returns for the asset class.

Another consideration that weakens the case for venture’s outperformance is that the HJKS data set likely overstates average venture returns. Burgiss returns data used in the HJKS Paper is based off of investment returns from LPs using the Burgiss platform. Over 1,000 LPs use the platform including pensions, endowments, family offices, and other institutional investors. The professionalism implied by LPs paying for the service most likely means a venture firm of a minimum quality is partnering with the LPs in the sample. The average AUM of venture funds in the sample is $226M ($300B over 1,329 funds) also implying a certain level of quality in GP given the amount of funds raised. Removing, what is likely, a material number of underperforming managers would positively skew the returns reported in the sample. Given the difficulty tracking private markets returns, Cambridge’s venture index data also likely has some degree of performance inflation given the selection biases of the types of GPs and LPs contributing to their data set.

While almost a decade old, the Kauffman Foundation’s 2012 We Have Met the Enemy and He is Us report paints a less optimistic picture about outcomes from a large venture portfolio.

“The cumulative effect of fees, carry, and the uneven nature of venture investing ultimately left us with six-nine funds (78 percent) that did not achieve returns sufficient to rewards us for patient, expensive, long-term investing”.

-Kauffman Foundation, We Have Met the Enemy and He is Us

Venture can be a game worth playing, but you need to be in the winners. The hope of excess returns with average outcomes is most likely overrepresented in the HJKS Paper given the selection bias of the data used.

Low Hanging Fruit

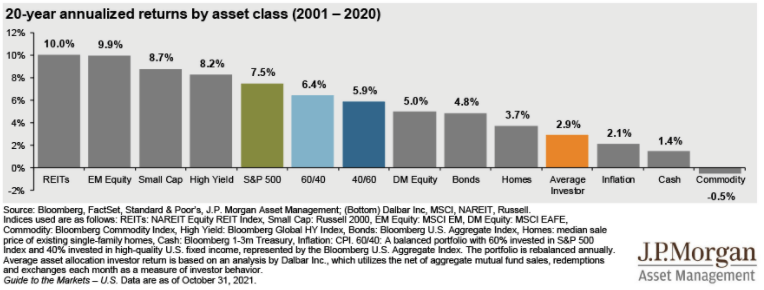

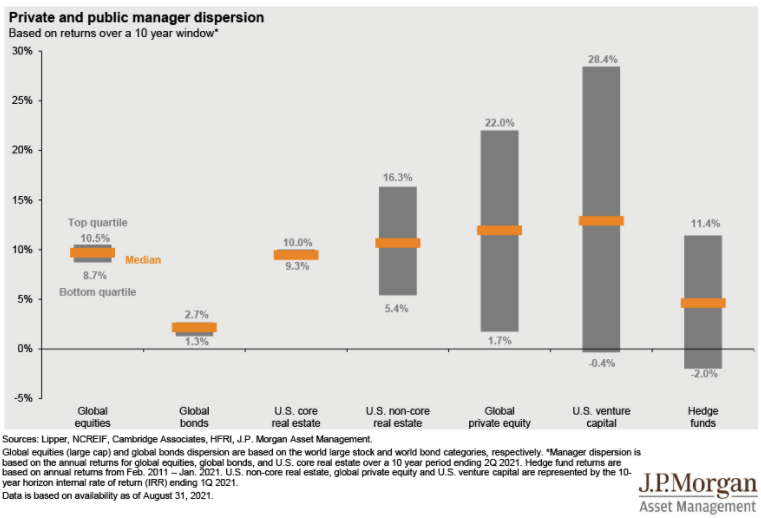

I find the narrative that being unable to access venture capital, or alternative investments generally, has a meaningful impact to financial outcomes of individuals to be disconnected from the challenges of median retail investors. Below is a chart from the October 2021 JPMorgan Guide to the Markets. The chart shows that the average investor’s return outcomes aren’t exceptional and there are liquid investment options that would materially improve the financial outcomes for the average investor before even considering adding alternatives to the portfolio.

Getting individual investors to achieve the returns of a 40/60 portfolio of stocks and bonds, let alone 60/40 equities and bonds or the S&P 500, would double their annual realized returns. The HJKS paper notes the venture asset class underperformed public markets for the 1980s and from 1999 to 2006 meaning that venture outperformance may not happen for a decade despite the liquidity difference. Given existing behavior by retail investors, creating products or companies that can effectively address the challenges of achieving market outcomes with easily accessible liquid investments would be more relevant and impactful for the average investor than changing regulations to allow people access to venture capital or alternatives with a nominal allocation.

I imagine some will present the case that robust secondary markets are a solution to solve for liquidity and risk management issues allowing more practical investment by retail investors into the venture asset class. Cost effective and liquid secondary markets would certainly be a benefit. Potential cash drag issues and forced selling in secondary markets to meet potential redemptions raises questions if there is a structure to invest in alternatives that would allow the retail investor to outperform public market alternatives. Given the precarious savings position of many households, redemptions would likely come in times of economic stress with negative impacts on liquidation prices of illiquid assets in forced sale environments. Maybe there is a potential product similar to a lifecycle fund that has a broad allocation with a piece of the portfolio being allocated to alternatives that reduces the potential liquidity stress in times of market stress with high redemptions. A single product focused on venture or alternatives would have potential challenges relative to more liquid alternatives in times of heavy redemptions.

The Adverse Selection Problem

Based on the returns data presented earlier, the real case for venture investing helping materially change the wealth creation ability of retail investors is for the average investor getting access to the RIGHT venture funds or a structural change in asset class returns going forward. I’ve expressed my skepticism of venture asset class level returns being structurally different in the future relative to the past. Data on performance persistence of high performing funds is meaningful, but how likely are these select organizations to open access to their platforms when they already have a group of institutions willing to provide the GPs with as much capital as the GP desires?

As a hypothetical, let’s say some vehicle existed allowing retail investors to participate in venture and a there is a robust secondary market for shares allowing the fund to have liquidity to meet potential redemption needs. What businesses that has a variety of capital options would choose a term sheet from this type of vehicle relative to a more traditional fund structure? The cap table of the business could be less stable due to the potential of liquidations needed to meet fund redemptions. All things equal, you imagine a top tier entrepreneur would avoid taking capital from this type of structure unless the amount was of no true consequence to influence the business relative to other options. Access to the best entrepreneurs is part of the underlying magic to create enviable returns for the exceptional venture organizations. One could say this type of fund could pay the entrepreneur more for access, but we already have Tiger Global out there vacuuming up deals with more aggressive pricing and they, along with similar types of strategies, lack the uncertainty that comes with a fund that would likely have to meet redemptions.

The best venture firms are more than capable of raising additional capital as seen by the expansion of the franchises over recent years. They don’t need the money. The groups that have the need for capital are often GPs with middling or poor investment track records and emerging managers. Not exactly ideal hunting grounds for individuals that, on average, have trouble committing to index funds. Top tier venture firms could potentially carve out a piece of their allocations or create more retail friendly vehicles like a closed end fund, but their existing investors are more attractive partners than retail investors. I would be remiss to mention, that there are some non-accredited investors that do have access to some top tier venture funds through pension benefits for those that are lucky enough to have that kind of retirement plan.

We have yet to address to issue of scale. The reality is even with the increase in size of the venture industry, there are only so many exceptional outcomes available for investors. 2021 will likely be the first year the venture capital industry will raise over $100B based on Pitchbook data. For simplicities sake, lets assume top quartile returns tie to the amount of capital raised and $100B is raised in 2021 which would have $25B of committed capital from the year achieving top marks. That’s ~$75 per person of top quartile venture investing commitments available for 330 million people on an annualized basis.

“There are not enough strong VC investors with above-market returns to absorb even our limited investment capital.”

Kauffman Foundation, We Have Met the Enemy and He is Us

Having Your Cake and Eating it Too

While not explicitly stated, I believe those that trumpet retail needing access to alternative investments are making the case that their companies are positioned to play by a different set of rules relative to publicly traded businesses. The creation of liquid secondary markets and access to retail investors sure looks a lot like being a publicly traded company without some of the costs required to be listed. One future that would allow retail to share in the wealth creation of some of the exceptional venture funded businesses would be to go public earlier than has been the case for many of the most exceptional companies built over the last decade. A couple of considerations here could be changes in the requirements or costs to go public, changes in preferences by entrepreneurs, or changes in fund structures that allow early stage investors to hold public shares longer that might adjust the calculous of when a company would choose to go public.

The Grift is Out There

I don’t sense that very successful venture investors appreciate the shenanigans that happen in the less reputable portions of early stage capital markets they are likely lucky enough to avoid. The Grift is always out there and there will always be people willing to sell their integrity for the option to make a few dollars. You can argue regulations might be too onerous, but there is a storied history of people willing to take advantage of others ignorance to make money and lower information disclosure requirements increases the opportunity set for these shady characters. Just because you’re smart enough to see the fraudsters coming, doesn’t mean everyday people will be.

Returns data shows retail investors struggle to get outcomes in-line with basic index strategies. Financial outcomes don’t inspire a great deal of confidence that retail investors will have the ability or interest to invest the time to effectively research which fund managers (that would even take their money) would succeed, identify attractive markets for a company’s product, or have a sense of who might become a great founder. Lacking these skills would put normal people at high risk of being swindled, potentially with their life’s savings. They can’t afford to lose $10K unlike others that are have more wealth.

The Yale Model Wasn’t Designed for the Everyman

Let’s assume realized venture returns for retail investors would be in excess of what can be accessed through public markets to consider the ability of a retail investor to capitalize on venture outcomes. The reality is the financial situation for most people doesn’t align well with the prospect of locking up capital for 10 years outside of a nominal allocation. Information sources from Charles Schwab, Fidelity, and JPMorgan Chase are used to paint the best picture I could of the median household’s finances to discuss the practically of long-lived illiquid investments. Financial returns realized by individuals also show there is substantial room for improvement in investment outcomes for the average household before even considering the need to use illiquid alternative investment to potentially enhance returns.

According to Charles Schwab’s 2019 Modern Wealth survey, 59% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck, 44% typically carry a credit card balance, and only 38% have an emergency fund. Not exactly a position of strength to tie up capital for extended periods of time. The same Schwab survey asked people what they would do if they received $1 million. 54% would buy a house first. Additionally, respondents would use funds to reduce debt (28%), invest (23%), and save (21%). Liquid assets are best served to address many of these goals given most individuals probably don’t want to wait around for a decade to pay down their debt or attempt to purchase a home for their families.

Investment strategies should be informed by their personal goals. Venture is unlikely to be a strong solution for these goals consideration the financial position of most people. Decade and longer lock ups would need to be handled in retirement accounts for the majority of people given their financial situations.

“Many VC funds last longer than ten years – up to fifteen years or more. We have eight VC funds in our portfolio that are more than fifteen years old.”

Kauffman Foundation, We Have Met the Enemy and He is Us

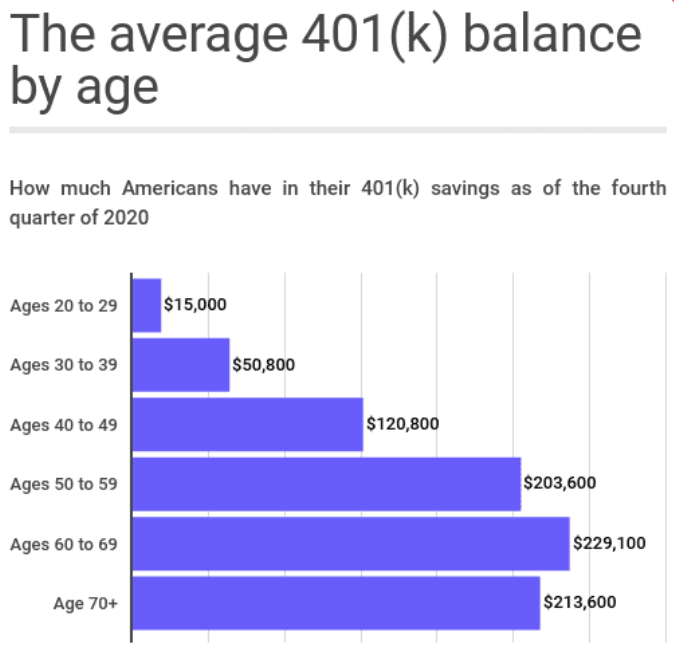

Data for retirement savings also puts into question the impact of illiquid investment strategies for median households. The chart below shows the average 401(k) savings balance for individuals based on data from Fidelity Investments. Savings accumulators in the early phases of the life have balances that wouldn’t allow for material contributions towards venture or other alternative investments, either via individual companies or funds. Those with larger balances have more leeway to manage the investment duration typically seen in early-stage investing based on the amount of capital they have, but they are closer to retirement and likely have upcoming needs to help fund their lives from those assets. Having ~$200K in your 60s to last you the rest of your days doesn’t afford the luxury of keeping a meaningful portion of your savings in illiquid securities.

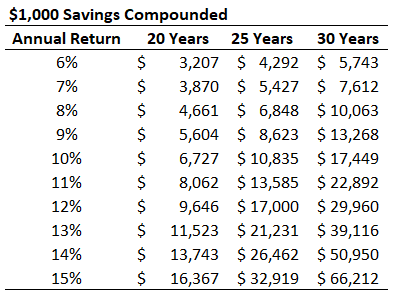

That’s not to say higher returns don’t matter and can’t make a difference. Below is a table showing the amount of money a $1,000 investment would turn into over extended periods of time based on different constant rates of compounding. $20K-$50K more in assets can be a big deal for many savers, but that wouldn’t make people in this situation wealthy. As discussed previously, I’m skeptical of the venture’s asset class as a whole to outperform liquid tech focused indexes and believe the structure of funding in alternatives creates adverse selection problems for the retail investor that increase the barrier to outperforming over time.

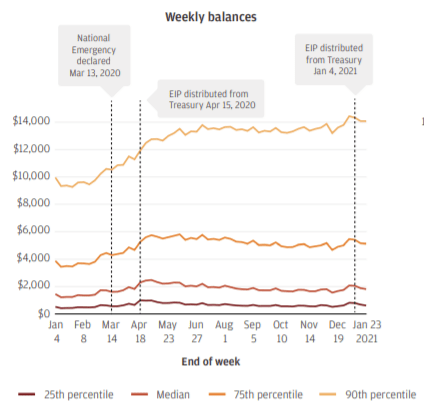

Individual’s after-tax savings has even less practical application to venture investing. Below is a chart of weekly checking account balances from JPMorgan data. The 75th percentile doesn’t even clear $6K. One might argue retail savers would have more assets in brokerage accounts. While fair, I wasn’t able to find good data on the average balance of these types of accounts and believe the checking data aligns with the picture that most American’s are living paycheck to paycheck. Who can commit to locking up taxable capital for a decade when their savings are in such a fragile state?

The Case for Choice & The Series 65

In my view, the strongest case for access to venture capital and alternative investments by everyone is the argument from choice. If you are ideologically consistent about prioritizing freedom of decision making in your views, this perspective is tough to argue against. This case is less common in the web spaces where advocates for broader access to alternatives share their views. Alternatives champions tend to emphasize other arguments like higher returns or democratizing investing (I view this as different than the case for choice), which I believe are missing the bigger picture.

Expanding the accreditation rules would most likely benefit younger high earners that are below accreditation standards. They are likely more motivated to learn about early stage investing and have extra capital to invest. This cohort has a path forward under the current rules. They can afford to take their Series 65 to gain access to investments requiring accreditation. A nominal barrier of entry like a test is probably a good thing given the amount of Grift happens at the lower end of private markets. The Series 65 isn’t hard, it just takes a little time and money.

*Edit on February 27th, 2022.* The Series 65 accreditation requirement is to be licensed, which also requires registration with the SEC. I can’t speak to the specifics, but this post by Nate Leung covers his registration journey. Get ready for paperwork.

Closing Thoughts

Attempting to put a bow on everything, the reality is many people struggle to get comfortable with even an S&P 500 index fund. They aren’t interested, procrastinate, get scared, or just don’t care about investing decisions that much or they would be closer to balanced portfolio returns. There is room for improvement using existing liquid assets before even needing to explore alternatives. Tech forward indexes provide an opportunity for retail investors to achieve returns roughly in-line with the venture asset class. The venture industry’s best performers lack the scale to move the needle for the bulk of savers. The lock up aspect of illiquid assets tends to only fit retirement savings goals for normal people. Let’s help the retail investor get the most out of liquid, low cost, off the shelf, investment options before we worry about further complicating their financial lives.